November 15, 1983 Seoul, South Korea

Boiling water. It is such a mesmerizing thing…. watching a myriad of tiny bubbles form out of nothing from the bottom of the pan, billowing up through the water column with dozens of its friends and bursting forth with a puff of steam in its dying moment. It is one of the many reasons that since as long as I can remember, I have been drawn to watching things happen the kitchen. I would love to watch Mom cut with a knife, mix bread with her doughy hands, and cook things in steaming pots. It was a full sensory experience punctuated by the skill of a talented cook. The sound of a knife bearing down through a crisp carrot; the vivid palate of onions, leafy vegetables, eggplant, carrots, squash and potatoes diced and splayed for the pan; the lifting aroma of garlic, onion and grated ginger sautéing in a roasted sesame seed oil. And the taste… the taste! There are few human pleasures quite as desirable as an excellent meal.

So one fateful evening, Mom had started to cook dinner after a busy day in language school and left for a moment to go check on something elsewhere in the house. I knew that I was not allowed to be next to the stove, especially unattended, but my desire to see the cooking in action was greater than my three-year-old will to follow the rules. I fetched a three legged stool, pushed it over to the stove and carefully climbed up to the top of the stool where took my usual Korean position of squatting. As I was squatting there, watching the boiling action in the pan before me, I heard Mom’s voice call out from behind. “Joel David!” Quickly, and without thought, I tried to hop off the stool. Unfortunately, this was a three legged stool, and as I jumped, the stool simply fell out from under me. I found myself in free fall, and in an instant, one of my arms caught the pot handle slightly sticking out over the edge of the stove. A split second later, I landed chest first on the kitchen floor with the boiling contents of water and macaroni spilling onto my back. “DAVID!” Mom called out with one of those other-than-human sounds that imprint the emotion of the moment into your memory. Dad rushed in and took note of what happened. In one fell swoop he picked me up and charged to the bathroom, turning on the shower and plugging the bathtub to fill with cold water. The boiling water had soaked into my shirt and pants, and Dad quickly removed my shirt as the cold water poured down on top of me. I protested my father’s actions! First I was burned and now I was going to be thrown into a freezing cold bath, and I didn’t see the point of needing an ice bath at this moment in time at all. I remember hitting the water and taking the short stuttered breaths that accompany a dive into cold water. I struggled to escape, but Dad was unrelenting. He pushed and held me down into the water even as the spigot flowed more cold water into the tub. Then suddenly, in a mixture of boiling, freezing and pain, I passed out. We would find out later, that Dad’s act was instrumental in saving my life, the first of several circumstances God would use to save me.

Since there was no ambulance service that Mom or Dad could call, and as we had no car of our own, they called some friends up the street who had a vehicle. Removing my now limp body from the bathtub, my skin collecting in its ceramic base, Mom wrapped me in a clean sheet while Dad loaded me into the back seat of our friend’s car, on top of Mom’s lap to head to the hospital. Momentarily I awoke from unconsciousness during the ride, complaining about the pain of the sheet pressing against my now raw back, and then passed back into the black stillness again. My parents arrived within minutes at the Severance Hospital in Seoul where the staff ushered me in, installed an IV, and began the process of debridement–the process of removing what was left of the burned skin on my back. “Did you rinse him with distilled water?” the doctor asked? “No, just the tap,” my Dad replied. I came to but just for a moment to see a flash of reality. I was laying on my stomach drenched in white light. Screaming. The medical staff were working above me in a crowded emergency room, my arms were being held down in response to my sudden and unexpected awakening. And again, I welcomed slipping into darkness again. After the process was complete, they dressed the area with sterile bandages and wheeled me into a hallway where my parents were told to wait. While it is true that the hospital in question was a large and busy one, it might equally be true that the doctors knew the likely outcome of my condition. At only three years old and having sustained significant 1st, 2nd and 3rd degree burns on my back, neck, arms and buttocks, it was likely that I was going to be dead in several hours anyway. A Korean doctor came by to tell my Dad that there were no rooms available in the hospital, and suggested that since we were Americans, he could call the 121 Evacuation Hospital and try to get in as a civilian emergency.

The 121st Evacuation Hospital (now called the Brian Allgood Army Community Hospital), is inside of Yongsan Garrison located in Seoul. Originally activated in 1944, it had been a semi-mobile unit on the forward line during WWII and the Korean War. In the event of a war with North Korea, it would be on the front lines of treating the wounded again. Dad used the emergency room phone and called the facility, shouting over the background noise of the hospital to explain my need. Several minutes later, clearance was given for a civilian emergency and a Korean ambulance was called to transport us there. This would be the second circumstance God used to save me.

It was November and very cold. The Korean ambulance had a hard bed, but no working heater, no IV holder, no patient belt, and no blanket on the table. I was bandaged but had only a thin gown to keep me warm. Mom guarded me from falling off the gurney with one arm while holding the IV in the other, trading off with Dad. The traffic was heavy and there was no priority given to emergency vehicles in those days, so thirty minutes later, we arrived at Yonsan garrison where an all-equipped ambulance was waiting. The medics quickly transferred me to the gurney and inside, then sped lights and siren to the 121 Emergency Room. As we arrived, the doors flew open and a doctor, dressed in a green gown took charge. “What bottle is he on?” he asked, referring to the IV. “The first,” Dad answered. Frustrated, the doctor told the nurse to reset a new IV as they raced down the corridor, leaving Mom and Dad behind. The Korean IV unit, it seems, was incompatible with those used in the States, and smaller. They later informed Mom and Dad that I was already a liter of water short from where I should have been.

Hypothetically speaking, if given the option to pick any doctor in the world to treat my case, it would be logical to pick an experienced burn surgeon – someone with great experience treating people with major burns. In reality however, these doctors are exceedingly rare, normally found at large hospitals with specialized burn units. But upon arriving at the hospital that evening, the doctor assigned my case happened to be one of the best. He was recently transferred from the Sam Houston Burn Center and was skilled in all the latest techniques. This would be the third circumstance God used to save me. I was again rushed to the operating room. They removed my existing bandages, set new IV lines and started a new round of debridement. I had been unconscious for awhile now, likely due to loss of fluids, but awoke again to see a flood of white light and people working above me. It was short lived, a few seconds at most and slipping into the darkness again was a welcome relief. The doctors finished their work, applied a new and expensive anti-microbial silver ion ointment onto my burns and wheeled me into a small private room where I could be isolated and monitored. They laid me on my front side on a special bed that had a canopy similar to an old covered wagon so that the sheets wouldn’t come in contact with my burns. In total, more than half of my back as well as parts of my left arm, most of my buttocks and my neck were affected by third degree burns. The rush was over. The work was over. Now all we could do was wait.

My parents during this time had not been alone. After watching me disappear into the hallway, they had turned around and were amazed to find some of their friends standing at the side of the room. Colonel Thar was a friend of folks from the church in Stillwater; Kathy had been befriended by Mom on the base in Korea, and the hospital nurse was C&MA by background. All had somehow heard about my accident and had gathered to offer their support. My parents waited with their friends for several hours until my condition was known. My mother remained by my side, even then, while Dad took a taxi back to my brother and sister being watched by friends. Our field director called our missionary organization in New York with a request for prayer. Then Dad called his parents in Chicago. Call by call, the news spread across continents. This was long before the days of e-mail or the Internet, but people knew how to get the word out. Hung from fridge magnets or taped next to rotary telephones across America were phone numbers on prayer lists. The prayer chain leader would receive the call, hear the news and pass it on to the next person on the list. In the coming hours, hundreds of people lifted up their prayers, and I would need every single one of them.

In my memory, it seemed like days before I regained consciousness. Mom stayed constantly by my bedside talking to me, praying for me, and sleeping in a chair beside my bed. Dad, together with my brother and sister, returned for frequent visits. When I did awake, I found myself laying on my front with one of my arms taped straight to a board, unable to move. The IV was my source of survival. It fed me. It replaced the fluids from my still porous skin. It offered me the morphine and steroids keeping me from the worst of pain. And given the crucial nature of my IV, there was an alarm that would go off every time I moved my arm so the nurses would come in and determine if the line was still working. I longed for the simple pleasure of being able to bend my arm, but every time I would try to bend it or move, the alarm would go off. The only consolation I had was that they would occasionally reset the IV to the other arm, allowing me to alternate which arm I could move.

Besides fluid loss, the second main concern was infection. My body was in no shape to fight anything off at that point, so everything had to be kept sterile. I wore sterile paper, slept on sterile paper, and had a very expensive silver ion lotion applied to my wounds. Despite my small size, I consumed the entire hospitals’ supply on hand in three days. I also had to take betadine baths. Developed for the U.S. Army, my “bath” was normally used to treat an adults’ leg or arm, yet it was large enough for my three-year-old body. Located in the therapy room, the tank was attached to a machine that would warm, circulate and aerate the anti-bacterial solution. My normal routine would be to get picked up out of bed, (kicking and screaming) placed in a paper gown and wheeled on a gurney down to the therapy room. They would take off the paper gown and I would be placed vertically inside the bath for 30 minutes. A nurse would do further debridement, as necessary, and then we would repeat the process in reverse.

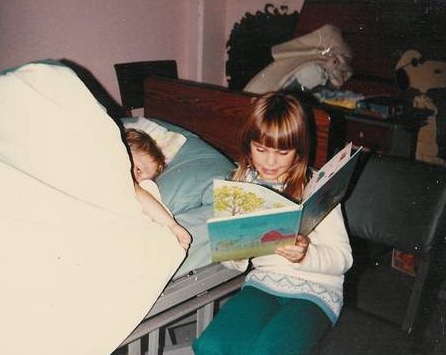

Two days after my burns my Mom overheard one of the nurses outside say to another nurse “I think he’s is going to make it.” Hearing this, she had mixed emotions. She realized it meant that my condition was improving, but also that my life had been hanging in the balance. Two weeks after this point, one of the doctors came in and handed a prescription to my Mom. It read simply, “Time to Go home.” After spending several weeks next to my side at every moment, it was time for her to see the rest of the family. I remember her leaving, laying in the darkness on my stomach, unable to move, unable to sleep. I would listen to the conversations of the nurses outside my door or watch the dim glow of lights against the wall. I constantly asked for the door to my room to be open, to feel connected to the world outside, and remember the feeling of sadness that settled over the room when the door was closed.

While moving was excruciating, it was also a crucial need of mine. Due to the extent of my burns and my age, the doctors did not have any skin to use as a skin graft, so my body was on its own to regrow the burn sites. However, when the skin did regrow, it would return in patches of thick scar tissue. If I didn’t keep moving while my skin was healing, the scar tissue would tighten, making breathing more and more difficult. To prevent this, the doctors made me get out of bed, wear a gown composed of sterile tissue paper and walk down the hall. Each part of it had a special form of torture. The paper gown would stick to my burns and moving would tear my delicate skin. Despite the morphine, I cried. My parents tried to ease the suffering by having me wear slippers and they would pull me down the hallway towing me with a blanket. I would grit my teeth and shred the sleeves of my gown to distract myself from the pain. And when it was all over, the paper gown would be removed, pulling off some of my newly grown skin with it.

Two weeks after my accident, on Thanksgiving day, I had my fourth birthday in the hospital room. Colonel Thar and his wife had brought get well cards from the children on base. Kathy brought a Baskin Robbins ice cream cake and my nurse friend had brought bananas which were terribly expensive off base at the time. The room was alive with people walking by my bedside to talk with me and bringing me gifts. I still couldn’t eat anything yet, but tried several licks of ice cream from a spoon and wound up sucking on a lollypop—my first solid food in several weeks. A clown appeared with balloons, sent by the Shriners Hospital all the way from Hawaii. They had heard about my accident and provided me with a year’s worth of 100% cotton clothing. I can remember my Mom crying at the news and wondering why crying at my birthday party was supposed to help. Later that same day, after things had quieted down in my room and the visitors were gone, Mom was sitting next to my bed when two uniformed men walked in. “This is Joel, a civilian, being treated for burns” the shorter man said, crisply. The taller man drew close and said hello to me, greeted my Mom, wished us well and left. Mom had recognized him immediately from the news but was startled by his presence and his penetrating blue eyes: there in my room was a four-star General Sennewald, the commander of the Korean and US Combined Forces. And everyone except me seemed excited about the event.

It was three weeks before I started “eating” anything. Meals were brought to my bedside and my parents tried every device known to parenthood to try to get me to eat. There were Choo-choo trains going into the tunnel, airplanes going into the hanger. Purée, jello and even ice cream appeared to tempt me. But I started out with something simple: Ensure. Ensure is like ice cream in a can (especially when chilled) and even today I find it delicious. I would have been content to drink Ensure for weeks, but for some reason, the doctors and my parents wanted me to eat other things, too. So Dad started to play hardball. You can have some Ensure after you eat something from your tray. I whined, flopped and cried, but Dad stayed firm. “We need you to actually eat something, honey” he prodded. My first solid food in weeks came in the form of some lettuce with French dressing… followed by an Ensure as a reward. My adult me would question the choice of French dressing now, as it is essentially super sweet ketchup with some vinegar added and I wonder what my younger me was thinking. Still, little by little, the adults began to win the war getting me to eat. After another week or two, I was eating normal meals and my body started to kickstart the whole digestion process again. Things were finally starting to mend.

By the end of week three, I was finally eating, drinking and moving without great pain. I still was having regular Betadine baths, but I at last had the freedom to start roaming the hallways of the hospital. I hadn’t seen any kids in weeks, but I found that there were other kids around. There was a kid’s room that had a selection of books and toys that I enjoyed. The nurses and doctors slowly became my friends instead of enemies and some would bring me treats like bananas. In the children’s playroom my folks were sometimes asked to translate doctor’s orders to visiting Korean parents. One time, for instance, Mom was asked to tell a Korean mom to shower her child before surgery the next day. How do I do that?, Mom wondered, since she knew the woman and her son were from a farm near the DMZ… and they probably did not even know how to use the shower.

My discharge came 28 days after I had been burned. While my body hadn’t fully healed, the recovery I needed did not require hospital treatment anymore. The skin on my back, while thin, had regrown. I was able to eat and drink on my own and did not require any drugs or specialized care. It was time to go home. During my hospital stay, I had stared longingly out of the hospital windows at a small blue metal playground sitting lonely next to the building. Upon discharge, I asked Mom and Dad if I could play for a moment, but my request was denied. For the next several weeks at home, Esuk supervised me and enforced the activity restrictions given by my doctors. Twice a day my sister or Mom would help rub Silvadene cream at first and later, cocoa butter on my back in an attempt to moisturize the skin and prevent further scarring. And for the next year, I wore the 100% cotton clothing so nicely given to me by the Shriners in Hawaii.

In my follow up visits, the doctors told my parents to look into skin grafts when I was older if the scars were too much of an embarrassment. While I was frequently asked “what happened to your back, man?” by other kids, it was usually a source of pride and not embarrassment. Actually, the most embarrassing part was my Mom, who would frequently ask me to lift my shirt to show people “how well I was healing.” For years after in Korea and back in the States, my back was put on display. But as much as I may have resented it in the moment, I would listen to Mom tell the stories of how God had protected me, and knew my scars were a symbol of Gods care for me. In the thirty some odd years since the accident, my scars have stretched and faded. The best time to see them is during the summer when the burned areas resist tanning, forming a splotchy patchwork across my back and neck. But as the saying goes – out of sight, out of mind – so the poor people poolside probably worry about it much more than I do. While the memories and scars from those many years ago remain, my one thought from the experience was that God must have wanted me around for some reason. It would have been so easy for me to have died, and yet, God arranged all of the circumstances to keep me here.

I learned later that my burns had a major impact on my parent’s ministry. My parents had assumed that our Korean friends, like our friends in North America, would have been praying—they were, after all, some of the most devout people we had ever known. But it turns out they were never told. “I never mentioned it,” our friend told my parents, quietly and with his head bowed, the implication being that they would have lost face if he had. Missionaries and pastors, they were to learn, were supposed to be people of prayer. Bad things were never expected to happen to them because of their close connection to God. Instead of sharing their burdens, therefore, the pastors and their congregation tended to hide them. There were three main lessons they learned from these experiences. First, it meant that part of Mom and Dad’s ministry in Korea would be to include a theology of suffering: that God allows devout Christians go through pain and trails to grow their faith and for His purposes in reaching others. Second, they realized anew the fragility of life and the cost of discipleship. Life was precious, but following God was not a guarantee of success or protection. Troubles were part of “counting the cost,” “filling up the sufferings of Christ,” to accomplish His mission. And the perseverance we learned, along with the trust, would serve us in many other situations later on. Third, in their later ministries, in the Philippines and beyond, my parents would minister to Korean missionaries who were going though difficult times. On a side note, Mom missed a month or more of language lessons while caring for me in the hospital, yet she scored higher than Dad did in the final term grade. Korean teachers, it seems, would use grades for encouragement as well and not only as a mark of performance.

Thanks for following along! If you want to read other stories as part of this series, a full list can be found here: Child in a Foreign Land. If you are interested in following along, we have links for e-mails, Facebook, WordPress and YouTube on the sidebar of the website. If you want to share a link to this story/video, simply choose one of the buttons below this post.

© Divergent Life Media, LLC

Thank you for sharing your story, it brought me to tears. What an amazing account of God’s faithfulness!

LikeLike

I think I mentioned to your mother a while ago, but I also want you to know that I spent two years of mandatory military duty stationed at 121st general hospital. In my years (1997 ~ 2000), we simply called the place as 121st general hospital affiliated to the 18th medical company and I didn’t know that it has changed its name. I was one of the KATUSA (Korean Augmentation To U.S. Army) soldier, a unique system that R.O.K army and U.S. army shared to enhance and promote collaborations.

I first began my service there as a staff member who supports KATUSA soldiers but I soon transferred to a unit of 121st general hospital whose main responsibility was to fix computers and maintain the medical prescription system. It was around the new millennium and our unit was busy in preparation of infamous Y2K problem. I, therefore, travelled a lot, we visited every place medical units were deployed inside South Korea.

Looking back, years that I spent there was one of fun memory that still makes me smile. I met many good people and had opportunities to have exposure to a new and different culture. I also remember that my father mentioned about severe burn and he was deeply concerned about it. What a coincidence! It is so pleasant to know that now we share a space that we spent a while in different times.

LikeLike

It was fun to hear your memories of your experiences. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

When our lives are at their darkest moment, God’s light shines brighter and casts out the darkness. Your testimony of God’s loving faithfulness, moved me to tears. Restoration and God’s tender healing touch knows no boundaries.

LikeLike